Jill Seaman

Credentials

Humanitarian Cause

Healthcare And Food Security, Access To Healthcare, Provision Of Medical Services,

Impact Location

South Sudan

Occupation

Medical Professional / Co-founder Of South Sudan Medical Relief

Photo Gallery

About

Jill Seaman is a dedicated physician renowned for her relentless efforts in delivering and improving medical treatment for infectious diseases in Southern Sudan, one of the most remote, poverty-stricken, and war-ravaged regions in the world. Her work has primarily focused on combating neglected tropical diseases such as kala-azar (visceral leishmaniasis), which has claimed tens of thousands of lives.

When the situation in South Sudan escalated again in the spring of 2025, Dr. Jill Seaman thought she had left Old Fangak in good shape. For several months each year, the American physician works with the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation in Bethel, Alaska, delivering essential healthcare to remote Yup’ik Eskimo communities while continuing her humanitarian mission in South Sudan. But soon after she left, everything changed. “It was the 3rd of May,” she recalls. “I had just left, and they got bombed. Oh my gosh, they’d never been bombed before—there’s no military there, no reason for it. The only thing we had was the healthcare.”

The attack forced the community to flee to the nearby village of Paguir, where thousands sought safety amid a cholera outbreak and rising floodwaters. With no one left to maintain the dikes that held back the river, Old Fangak was swallowed by water. “All the huts collapsed. The TB huts collapsed. My home collapsed too,” she says. “Everything we built was gone.”

It was a devastating moment, coming just as decades of work were beginning to bear fruit. For the first time, students were graduating from secondary school, some continuing to nursing programs abroad and returning to serve their communities. When cholera struck, locally trained staff acted immediately, following protocols without waiting for her guidance. “It turned out that one of our staff doctors was a child we treated years ago,” she recalls. “He told me he wanted to do what I was doing, and I told him he’d need some schooling, and he decided to go to school. And he’s now back with us as a doctor there. We have lots of stories like that.”

Dr. Seaman’s journey began long before Old Fangak. Born and raised in Moscow, Idaho, she studied at Middlebury College in Vermont before earning her medical degree from the University of Washington in 1979. After completing her residency in family practice at the University of California, San Francisco program in Salinas, California, she moved to Alaska, working in Bethel with the regional Indian Health Service. Driven by a desire to serve beyond her community, she applied to the International Rescue Committee in 1984, treating Ethiopian refugees in Sudan.

“It was around the time when songs like We Are the World were just starting to inspire people,” she recalls. Later, she studied at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, earning a diploma in 1989. “I think everybody has to follow what they think might be a way to interact with humanity and help,” she says. “Being a doctor gave me so many choices of where I could be useful. I didn’t want to live in a big city—I wanted to be part of a community and contribute to it.”

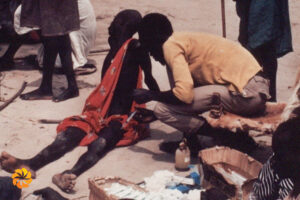

After London, armed with new expertise, Dr. Seaman joined Médecins Sans Frontières to respond to a devastating visceral leishmaniasis outbreak in Sudan. Visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar, is a severe parasitic disease that affects internal organs and can be fatal without prompt treatment. “In the southern part of Sudan, we did a survey and found that probably 50 percent of the population had already died,” she says, adding that if such a tragedy had happened elsewhere, the world would have definitely known about it.

Over the course of a year, they treated more than 10,000 people. At the height of the epidemic, the pressure was relentless. “They told me, ‘Jill, you just cannot make people work this hard. You have to choose who you’re going to treat and who you’re not going to treat,’” she reflects. “And man, that’s not something I’m comfortable with.” Refusing to turn anyone away, she and her colleagues restructured their work with the help of locals, refining treatment protocols with limited supplies and immense determination. “It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. We started with a 10% death rate, then 8, then 7—and later, when we got facilities and intercurrent treatment of illnesses, it went down to 5 percent. It dropped below 3 only when we began doing blood transfusions. Without treatment, it’s a 95% death rate.”

“Soon, the kala-azar epidemic was waning and people said, ‘You cured us of kala-azar, and now we are dying of TB. You have to help us.’ TB treatment in a war zone was not something that any international medical NGO was doing”, notes Dr. Seaman. “Together with a Dutch Nurse practitioner Sjoukje de Wit, we thought, well, a couple of crazy young ladies could start a tuberculosis program in a war zone. If it didn’t work, people would just laugh and say we were silly to do something like that. But if it worked, it could spread.”

The risk paid off. In a remote, relatively peaceful area, they built what became the South Sudan Medical Relief program, rooted deeply in the community it served. Later, Dr. Seaman and her team relocated to Old Fangak, a small village along the river. “It was better there,” she explains. “People had water to wash, we could get water for drinking, and we could dig wells. It was a much better place in terms of health of the population—and we’ve stayed there ever since, until May 3, 2025.”

Decades of work in Old Fangak taught Jill the limits of control and the quiet power of compassion. “I can’t build a first-world hospital that treats everyone. But you can do a lot just by witnessing and sharing humanity. When a mother loses her child, both our hearts are broken, not just one. It doesn’t make it better, but it reminds us we’re all striving in the same world.”

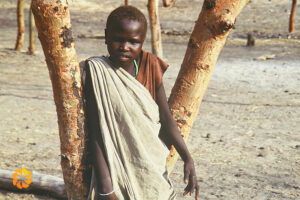

For her, hope revealed itself in unforgettable encounters, like meeting a little girl named Taban. “She came to us completely malnourished. We treated her for TB, gave her food. She was just too cute.” The girl eventually recovered and returned home. Years later, while visiting another clinic, a young woman approached Jill—it was Taban. “She had walked all day just to say hello. I couldn’t believe it.”

Dr. Seaman often shares Taban’s story as a reminder of why she continues her work despite the odds. “People say, ‘It’s good what you’re doing, but those people are all going to die anyway,’” she says. “And I understand where that comes from—you can’t solve everything. But you can give people a chance, a hope. Hope for health, so they can try to build a life.”

Hope in South Sudan has taken many forms—sometimes as simple as the sound of children singing. “We had a school in the village. Sometimes school kids would go singing through the village whatever song they’ve learned,” Dr. Seaman recalls. “They were learning to play, to think differently, not just to be warriors or helpers of warriors. I really think there’s very, very few people in South Sudan who’ve ever lived in a civil society. That was hope, because if you have health and schooling, maybe the future gets a little bit better.”

There were moments when peace felt almost within reach, but that fragile hope faded in May 2025, when Old Fangak was bombed and flooded by the river. “I really hope we get the school back,” she says. “But right now, people are just trying to make something work and stay alive. Our plan is to keep health going so we can find out what to hope for next.”

Being named one of the 2025 Aurora Humanitarians came unexpectedly, right in the middle of one of the hardest periods of Jill’s life. She sees the recognition as a way to draw attention to the work and the people that matter most. “People don’t really understand what’s possible until they meet someone who’s been there or hear their story,” Dr. Seaman reflects. “I think the interest sometimes comes because people see what the need is and what is possible. Nobody has all the answers, but seeing a way forward helps people find their own path.”

The information on this page was last updated on 10/28/2025 and was provided by the Luminary.

Additional Links